THE EVOLUTION OF LOCAL BARRIOS

According to Pedro Patricio in his book (Mandaluyong: 1837-1975), Mandaluyong has five (5) original barrios as per the first recorded census in 1903. From these five (5) evolved 22 sub-barrios which, like the original barrios, then became independent barangays.

Poblacion

This place used to be called “Buhangin” (sand) before it was named Poblacion because the whole stretch of the area, from F. Blumentritt St. corner of New Panaderos Extension up until the Catholic Church and the cemetery, was topped with sandy soil of about 2-3 inches thick.

Namayan

The first settlers of this place were Muslim Filipinos. They were later driven away by the Spanish colonizers who came to the place. Still unnamed till then, the inhabitants called it “Namayan” in memory of the original settlers of the place.

Hulo (San Pedrillo)

Hulo means “outer part” or “external” location of a barrio or town. When Barangka was still a sloping forest, Hulo was already a sitio with a few inhabitants. Early inhabitants of Mandaluyong used to call the place Hulo because of its remoteness of location. This place continued to be called as such until the name was officially adopted when it eventually became a barrio.

Buayang Bato

Located at the southeast shoreline of Mandaluyong is a small barangay called Buayang Bato. Its legend tells of an old Chinese man long time ago who, despite conversion to Christianity of his fellow Chinese nationals residing in this place, ridicules the religion.

One day, while the old man was on a boat crossing the Pasig River, the Devil decided to take him to hell. Transforming into a crocodile, the Devil swam towards the boat. The old man, who had never seen such a huge crocodile, was terribly shaken. Realizing that the god he worships is too far away in China, he began to call on Saint Nicholas, whose statue he saw in Guadalupe Church, to save him.

Miraculously, the creature turned into a stone. Shortly after, the old man embraced Christianity. And the stone crocodile, it is said, could be seen during low tide at the bank of the river near the Tawiran (ferry station). The place came to be known because of this stone crocodile, ‘buayang bato’ in Filipino.

Wack-Wack

At the northern part of the city is Barangay Wack-Wack, known internationally for the Golf and Country Club it hosts. Stories tell that many years ago, the place was a vast grassland which was home to numerous large glossy black birds called “uwak” (crow). It was from this “uwak” that the name “Wack-Wack” was derived.

Barangka

Alongside Brgy. Buayang Bato is Barangka, then a single barangay but later subdivided into four (4) barangays during the time of Municipal Mayor Bonifacio Javier: Barangka Ilaya (uptown), Barangka Itaas (Upper) Barangka Ibaba (Lower), and Barangka Drive.

It was said that at the time when the Philippines was under the Spanish Regime, there lived an old woman named Barang who had a young daughter. The daughter was in the rice fields when she was attacked by a man. As she was calling her mother for help “Ka Barang, Ka Barang!” the surrounding hills echoed her cry which was heard by the Spaniards. And as the story goes, the place came to be called Barangka.

Hagdang Bato

This place is located on the uplands where steps are carved in its rocky hills and used as stairways. However, this place is more popular for its historical significance because of the role it played during the Spanish occupation.

It was in this place, where, on August 28, 1896, Andres Bonifacio issued a proclamation setting Saturday, August 29, as the date of the attack on Manila. At 7:00 o’clock on Saturday evening, Supremo Andres Bonifacio held a meeting which was attended by more or less 1000 “Katipuneros”. Weapons were distributed during this meeting and the revolution began as church bells tolled.

Zaniga (Saniga)

Lying on the lowlands adjoining Hagdang Bato is Saniga which used to be a marshland teeming with various fruit-bearing and hardwood trees. The place was home to many local heroes who gallantly fought during the Spanish, American and Japanese occupations, thus, some of its streets are named after them like Capt. Magtoto St., Capt. Gabriel St., and Pvt. E. Reyes St. During the 1960’s and 70’s, progress gave way to concrete roads and houses sprouted in neighboring areas. This neighborhood was called New Zaniga Subdivision, while the original Saniga was renamed Old Zaniga.

Plainview

As the name implies, this place is a vast plain used to be planted with rice and corn. The place abounded with trees and was popular to bird hunters. Once, it was a private property developed by its owner, Ortigas, Madrigal and Company, into a subdivision providing a site for the municipal center. Afterwards, it was made a separate barangay through a Presidential Decree. Its original name, Plainview, was retained and at present, it hosts the Mandaluyong City Hall and other public institutions.

|

Mandaluyong’s Original Barrios and its Succeeding Subdivisions |

||

|

Original Barrios |

Supling na mga baryo |

Katutubong mga sityo |

|

Poblacion |

Pag-asa |

Buhangin |

|

Barangka |

Barangka Itaas |

(dating pangalan ng mga sityo ginawa ding pangalan ng mga supling na baryo) |

|

Hagdang Bato |

Hagdang Bato Ibaba |

Paso Bangkal |

|

Namayan |

Vergara |

|

|

Hulo |

Plainview |

Mauway |

|

Source: Pedro D. Patricio, 1976, Mandaluyong: 1837-1975 |

||

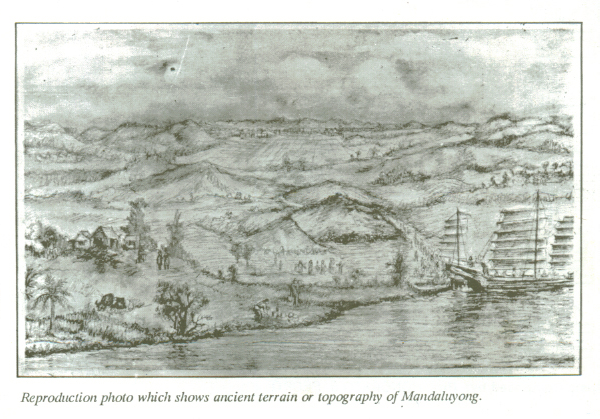

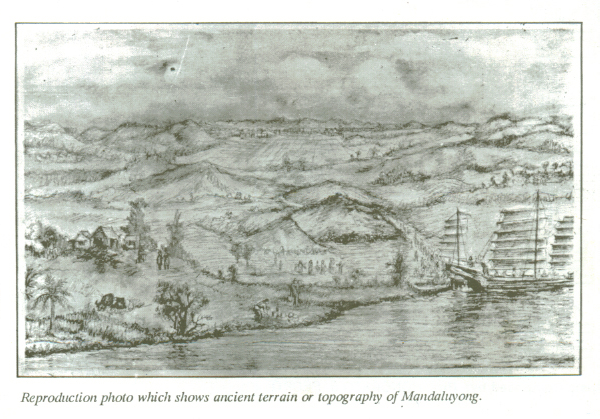

THE ORIGIN OF “MANDALUYONG”

Inhabited for centuries and rich in culture, Mandaluyong City has lots of stories to tell — heroic undertakings, cultural and supernatural beliefs, romance and more. The following stories tell of unusual names of places and features that inspire curiosity among inhabitants (old and new), researchers, and passers-by. One story tells of the early days when the place abound with a kind of tree called luyong from which beautiful canes and home furniture were made. Another claimed that the Spaniards named the place Mandaluyong based on the report of what a navigator named Acapulco saw that the rolling hills were frequently lashed at by daluyong (“big waves from the sea”). This seems to give credence to traditional stories before the coming of the Spaniards that giant waves from the sea lashed at the adjoining hills of the vast lowland, referred to as “Salpukan ng Alon”. Father Felix dela Huerta, a Franciscan Historian, observed that the rolling topography of this land resembled giant waves of the sea.

Romantic residents, however, peddled the story of a Maharlika named Luyong who fell in love with Manda, the lovely daughter of a barangay chieftain. The chieftain had no personal liking for Luyong and forbade his daughter’s marriage to him. Luyong overcame the objection of Manda’s father by winning a series of tribal contests which was the custom at the time. The couple settled thereafter in a place which was later called “Mandaluyong” literally named after “Manda” and “Luyong”.

POLITICAL HISTORY

1300s

Residents of Mandaluyong have always been known for their industry. Men did the laundry to the amusement of non-residents until shortly after the war, while the women ironed the clothes. These industrious people trace their roots to Emperor Soledan (also known as “Anka Widyaya” of the Great Madjapahit Empire) and Empress Sasaban of the Kingdom of Sapa whose son Prince Balagtas ruled as sovereign of the kingdom in about the year 1300. More than a century later, in about the year 1470, it expanded and was called the “Kingdom of Namayan” with “Lakan Takhan” as sovereign. The vast Kingdom comprised what are now Quiapo, San Miguel, Sta. Mesa, Paco, Pandacan, Malate and Sta. Ana in Manila, and Mandaluyong, San Juan, Makati, Pasay, Pateros, Taguig, Parañaque, and portions of Pasig and Quezon City up to Diliman that were then part of Mandaluyong.

1800s

Mandaluyong was first known as a barrio of Sta. Ana de Sapa which was part of the District of Paco, Province of Tondo. Named San Felipe Neri by the Spaniards in honor of the Patron Saint of Rome, it was separated civilly from Sta. Ana de Sapa in 1841. On September 15, 1863 San Felipe Neri established its own parish and under the administration of the Congregation “Dulcisimo Nombre de Jesus”, it constructed its own church, convent and school.

The Parish of San Felipe Neri played a significant role as a relay station for propagating the Katipunan during the 1896-1898 Revolution. It was in Barangay Hagdan Bato on August 28, 1896 where Andres Bonifacio issued a proclamation setting Saturday, August 29, 1896 as the date of the attack on Manila. It was also in this town that the revolutionary paper, “La Republika”, was established on September 15, 1896.

1900s

During the American regime, San Felipe Neri was raised to a first class municipality with five (5) barrios, namely: Poblacion, Barangka, Hagdang Bato, Namayan and Hulo. Under Presidential Act No. 942, it was consolidated with the municipality of San Juan del Monte and became the seat of government. For several months in 1904, San Felipe Neri became the capital of the province of Rizal.

San Felipe Neri was separated from San Juan and became an independent municipality on March 27, 1907. It was renamed the Municipality of Mandaluyong by virtue of House Bill No. 3836 which was authored and sponsored by Assemblyman Pedro Magsalin, then the Representative of the District of Rizal.

During World War II, Mandaluyong lost many of her people, among them were Catholic priests and civilians. Destruction was felt all over, but with the timely arrival of the American Liberation Forces on February 9, 1945, the municipality was saved from further damages. That day became a red calendar day for Mandaluyong marking its liberation from the Japanese Imperial forces by the Americans.

In the 60’s, Mandaluyong became a component municipality of Greater Manila Area (GMA) which became an independent entity called Metro Manila in 1975. Together with other component cities and municipalities, it has undergone significant physical and economic transformation. From a forestal town to a progressive municipality, Mandaluyong is now a highly urbanized city known to host most of the country’s best companies and corporations, shopping malls and hotels which are certainly world class in status.

Mandaluyong and the municipality of San Juan used to be represented in congress by a single Congressman. As it entered cityhood in 1994, Mandaluyong became a lone district with its own Representative in Congress.

2000s

Mandaluyong at the turn of the century was proclaimed by the city’s grand dads as the Millennium City, having come a long way from being a forested rolling hill to a bustling city of vibrant economic activities. It was recently named the new tiger city of Metro Manila, among other accomplishments.

Mandaluyong today is composed of 27 barangays divided into two political districts mainly by Boni Avenue and G. Aglipay Street. As of June 2018, there are 214,608 registered voters in Mandaluyong City, in which 58.69% are registered in barangays under District 1, and the remaining 41.31% are voters in District 2. It can be noticed that barangays with large populations also have the higher number of voters, like in Barangay Addition Hills.